The process is actually centuries old, dated back to 1805 when an Italian electrochemist, Luigi Valentino Brugnatelli, conducted and formalised the experiments using his colleagues, Alessandro Volta’s, voltaic pile, to facilitate the first electrodeposition. Decades of manipulation, and advancements in other fields, finally saw the Patent being issued in 1840. It continued to be adopted and developed across Europe by electrochemists, engineers and manufactures alike evolving into the process Tauranga Electroplaters uses today.

More HistoryElectroplating or electrodeposition as it is also known, is a process in which material is deposited onto a conductive component using electric current. The result is a thin layer, between 0.012 and 0.008mm, of a different material and its physical properties being transferred to the surface of the component or object. This alters its characteristics across four main categories.

· Increased wear resistance

· Corrosion protection

· Aesthetic appeal

· Physical size

As its name depicts the electroplating process uses electricity in dissolving and depositing of metal onto a conductive surface. Direct current is added to the circuit using a rectifier and positively charges the Anode which is made from the metal that will form the plating. The component to be plated is the cathode and is the negatively charged electrode in the circuit. Together they are submerged in an electrolytic solution where the electrodeposioning reaction takes place.

What happens? Here’s the magic, the current causes the anode to oxidise allowing, in our case the zinc, to dissolve into the electrolyte solution. Remembering that the dissolved zinc ions are positive these are attracted and deposited onto the surface of the negatively charged component,or cathode, as a thin layer of zinc. Sounds simple right? Not quite, for this reaction to take place a few things must be aligned perfectly. The preparation of the surface, the chemical composition of the tanks, the precise placement of the part, its relative distance from other parts and the anode, the electrical current, voltage and time in the solution. Combine these elements with experience, continuous chemical testing, and a desire for quality and you have the recipe for what many call one of the dark arts.

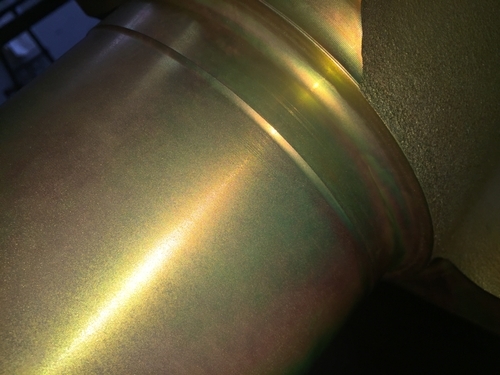

The zinc plating process is directly followed by the application of passivate or chromate, this is where the colour is introduced. Passivates and chromates are the same, and is used to coat the zinc post plating to increase it's corrosion resistance resulting in a high salt spray resistance, of up to 120 hours, and protect against white and red rust, the effects of surface oxidation. The process takes place in conjunction with zinc plating to convert the surface of the metal in to a mixture of chromium compounds which oxidise into a protective barrier. Zinc plating colour can vary greatly depending on the base material, polished or machined components produce a bright finish where black plate or sand blasted components will appear dull, in fact the condition of the surface at the start of the process is how it will look at the end this is illustrated bellow.

The colours offered at Tauranga Electroplaters can quite easily be split into 2 categories Silver and Gold, this however is where it tends to get confusing and often what is specified on drawings refers to the same thing expressed in different ways, here is a guide to some often misunderstood terms.

There is no passivation process that will not affect the colour of the component, commonly where ‘Blue’, ’Clear’, ‘Natural’, ‘Silver’ or’Trivalent (cr3)’ passivate is specified it is referring to a Clear finish. These passivates have a noticeably light iridescent blue colouring similar in certain light conditions to that of petrol on the surface of water. To achieve a true blue or any other colour a dye would be added. These Passivates provide good cost-efficient corrosion resistance.

Gold or Yellow passivate is a traditional finish not as widely used now but still offers a cost-effective way to achieve excellent corrosion protection. The darker colouring of the coating is often an indication of the amount of Hexavalent Chromium in the makeup of the solution the ‘Stronger’ the colour the better the corrosion protection.This process utilises Hexavalent Chromium (cr6) ..